Despite illness '˜if they asked me to go again I would'

The 56-year-old from Heron’s Reach, Blackpool suffers from a chronic kidney disorder which doctors say could be life-limiting and which Drew believes stems from the course of inoculations all forces endured before they were deployed to the desert.

“I had the full cocktail of drugs and it knocked me out for more or less 24 hours,” he recalled. “But on top of that I was up in Kuwait operating in all the oil smoke where day could turn into night in a matter of seconds and you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Within a year of coming back I was diagnosed and I’ve been living with it ever since.”

While many veterans of the 1990/91 conflict have sought recompense for Gulf War Syndrome, Drew refuses to play the blame game.

“I am not complaining because I signed up to whatever was going to happen,” he said at BAE Systems in Warton where he now works on the development of unmanned aircraft.

“What I’ve got is just a consequence of war.

“A specialist told me it would be life-limiting and probably be the death of me eventually. I am on constant drug treatment, but it doesn’t stop me working and I’m not disabled.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I am completely happy to tolerate it because I went into it with my eyes open.

And if they asked me to go again I would.”

Around a third of the 700,000 US troops who served are said to be affected. It is estimated 33,000 UK troops are suffering from illness as a result of the Gulf War.

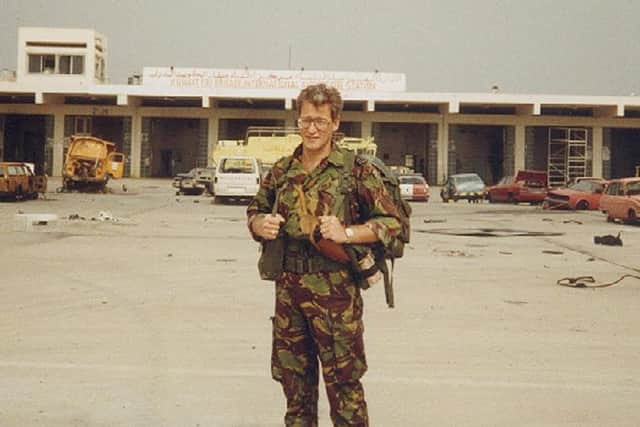

Drew was posted to Oman in the build-up to hostilities and then moved to Saudi Arabia and finally Kuwait as the invading Iraqi forces were driven out. He worked on Nimrod surveillance as an ops officer and went on sorties to pinpoint enemy radar positions and Iraqi mines.

“I live in Blackpool and I’m used to the fireworks championships every year,” he said. “Well one night in the very north of the Gulf it was just like that as the attacks were going in and the sky was lighting up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As soon as the button was pressed for the ground troops to go in it was staggering how quickly it all happened.

“When I was in Kuwait City hearing the gunshots going off, none of them were probably aimed at me, but you don’t know that at the time. I suspect in reality I wasn’t in mortal danger.

“I guess we all want to know how we will react to the fear of being in those situations and I’m lucky to have found out how I reacted. I also saw that, while we are all for Queen and country, the driving motivation of troops is not to let their mates down on either side of them.

“I’ve got to say I was fairly flabbergasted when I heard President Bush ordered a stop. Clearly there was still work to be done. But it’s not up to us, we’re just there to do the politicians’ bidding.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDrew, who left the RAF to join BAE in 2007, was in Kuwait City when it was liberated.

“Seeing the gratitude of the people was absolutely staggering. They couldn’t find the words to thank us enough. I was very proud we did it.”

Just 100 hours of fighting, but aftermath still raw

It was one of the shortest wars in history, with just 100 hours of ground fighting in total.

Yet the aftermath of the first Gulf War is still being felt, 25 years after it ended.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a conflict which introduced the world to a whole series of new terms.

Scud, Patriot and Cruise missiles came into common parlance.

And the war also coined phrases like “friendly fire,” “human shield” and “a line in the sand.”

It gave its name to a mystery condition known as Gulf War Syndrome which, a quarter of a century on, is still afflicting thousands of troops who served in the desert for their country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVeterans believe theirs was a war which has been largely forgotten – unlike the Falklands, Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns which have attracted far more attention from the media over the intervening years.

“Maybe if we had carried on to Baghdad and finished the job there and then we would have been remembered,” said one soldier from Lancashire.

He, like many of the troops who drove Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, suffered the frustration of being told by politicians to stop and go no further.

The “job” had to be finished 12 years later when another coalition of forces swept through Iraq and into Baghdad to topple tyrant Saddam Hussein.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo those troops went the glory, while the men and women of the first Gulf War melted away into history, only to be recognised briefly on the 25th anniversary yesterday.

The entire Gulf War lasted just short of seven months, from August 2, 1990 to February 28, 1991. But only a small portion of that was actual combat.

A coalition of 34 nations mobilised in reponse to Saddam’s invasion and annexation of Kuwait and the first phase, Operation Desert Shield, involved the build-up of forces in Saudi Arabia, a potential Iraqi target next door.

Britain sent more than 53,000 troops to the region, along with almost 2,500 armoured vehicles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt also sent out RAF Tornado and Jaguar aircraft, partly manufactured in Lancashire, to quickly establish air supremacy.

Throughout a tense stand-off during Desert Shield, Saddam held hundreds of civilians from western nations hostage in what became known as a human shield.

They included a couple from Blackpool, Maureen Wilbraham and her husband Tony who had terminal cancer.

Unknown to the Iraqis they also included a cousin of former West Lancashire MP Ken Hind who was a member of the British government at the time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the fighting began on January 17, now called Operation Desert Storm, the air bombardment of Iraqi positions in both Kuwait and Iraq was relentless.

The coalition flew more than 100,000 sorties in just over six weeks, dropping 88,500 bombs.

The RAF flew 126 missions in the first 24 hours.

The 66-strong Tornado force was later hailed as the “undisputed star of the Gulf War,” although seven were lost - six British and one Italian.

While Iraq’s air force was obliterated, Saddam’s troops still had the feared Scud missiles which were fired at Israel, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Qatar from mobile launchers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe coalition countered with Patriot missile batteries to intercept them.

By the time the allies actually put boots on the ground to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait, it almost became a rout.

Within 100 hours the coalition troops had put the enemy to flight and forced them back into Iraq.

However, the political decision taken by American President George Bush was to halt things there and a line was drawn in the sand - a line which would later be crossed in 2003 when Saddam was finally overthrown.